Introduction

Have you ever thought about the reason why water H2O usually occurs in liquid form while oxygen O2 is a gas? Powerful and invisible connections between the atoms, called chemical bonds, are the answer.

A chemical bond, in the most straightforward way, is the attractive force that keeps two or more atoms, ions, or molecules together. These chemical bonds are the basic reason for all chemistry and thus control the structure, properties, and reactivity of every matter in the universe.

What Is the Reason for Atoms to Bond?

Atoms bond in order to gain stability. It is like a trip to the lowest energy state possible. The majority of atoms, excluding the noble gases like Neon and Argon, are unstable by nature when they are isolated.

An atom’s stability is achieved by the adoption of a noble gas’s electronic configuration which in most cases implies having eight electrons in the outermost shell. This principle is known as the Octet Rule.

To obey this rule, atoms have two options:

- Give away their electrons to another atom or take from it.

- Form electron pairs with each other.

The nature of the interaction will determine the chemical bond type created, which then classifies us to the main types: ionic and covalent bonds.

Historical Roots of Bonding Theory

The concept of atomic connections took a long time to develop. It was a gradual transition from the early concept of “valency” (the combining capacity of an atom) to the current strong and quantitative theories.

Early Ideas: From Valency to the Octet Rule

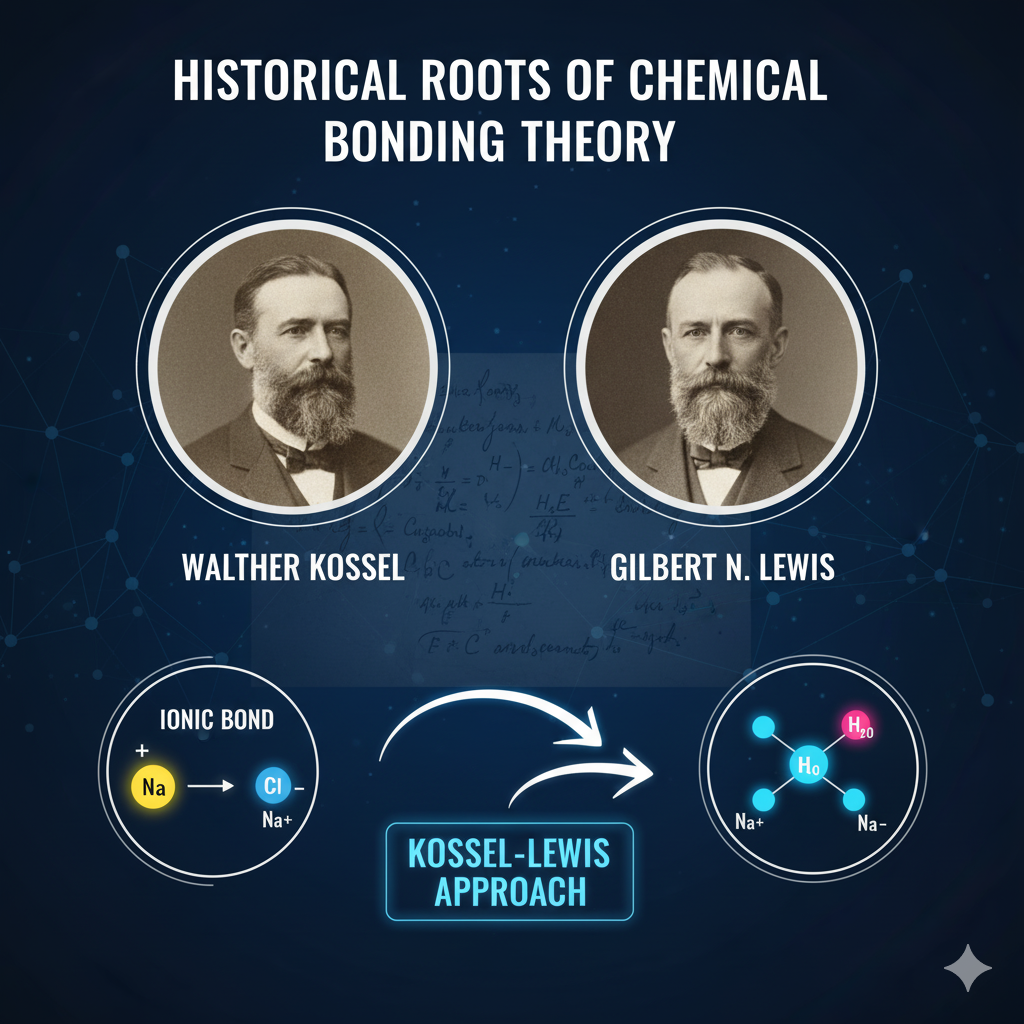

In the 19th century’s end and the 20th century’s beginning, two exceptional chemists were kept busy laying the foundation of the modern bonding theory:

- Richard Abegg indicating that there are different elements that tend to either gain or lose specific numbers of electrons.

- Gilbert N. Lewis redefined the domain in 1916 asserting that a chemical bond is then when the electrons are shared between the two atoms. He proposed the simple but very powerful Lewis dot structure to be used in visualizing the valence electrons.

- At the same time, Walther Kossel suggested a theory that was all about the complete transfer of electrons, and thus he explained the ionic bonds formation.

The trio of these scientists made the Kossel-Lewis Approach to chemical bonding popular which in turn controlled the understanding of the Octet Rule, the main factor behind almost all chemical reactions.

Main Types of Chemical Bonds

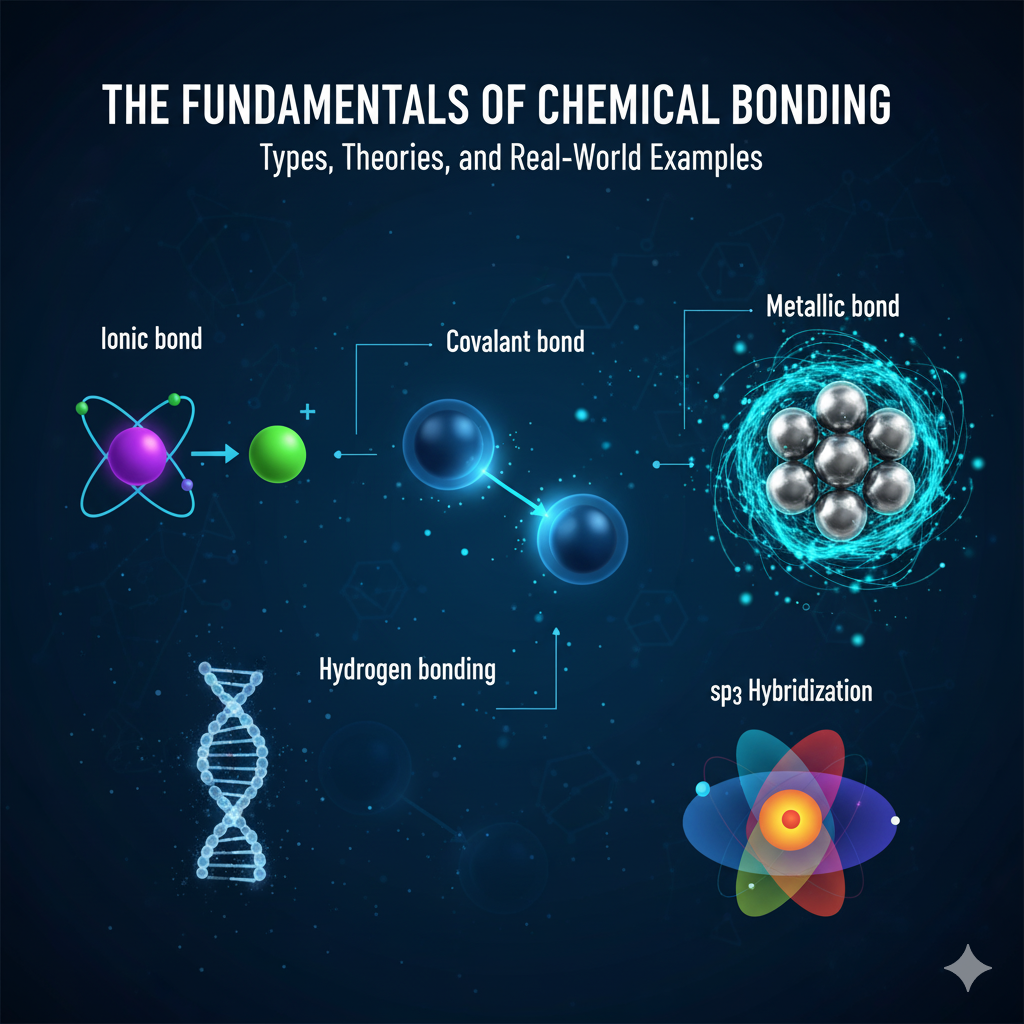

Mainly, during all bonding process, atoms achieve the stability through different mechanisms which leads to three main classifications of strong chemical bonds: ionic, covalent and metallic.

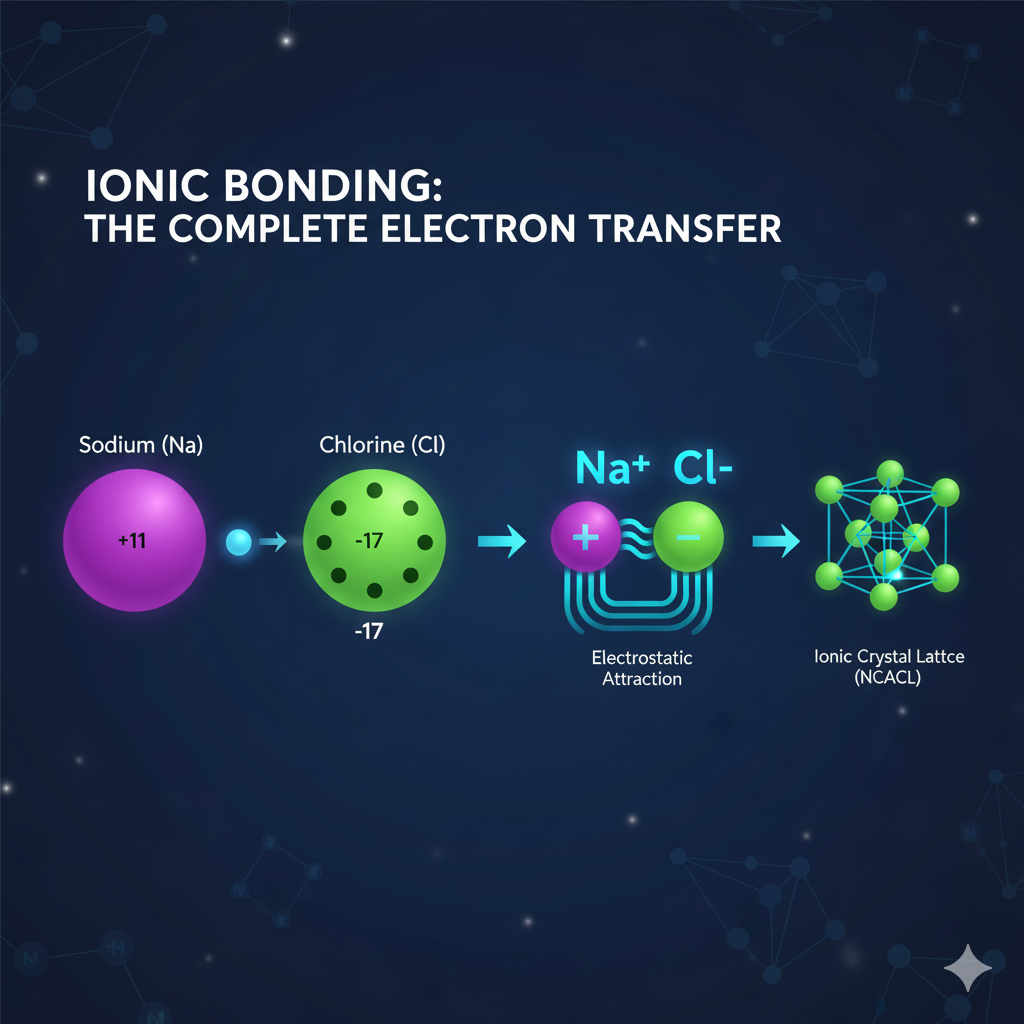

Ionic Bonding: The Complete Transfer

Ionic bonds are created in the event of a big difference in electronegativity (the atom’s ability to attract electrons) between two atoms. Usually, this happens between a metal (an element that loses electrons) and a non-metal (an element that gains electrons).

As a result of this, one of the atoms transfers one or more electrons to the other atom completely. The transfer leads to charged atoms called ions:

- The atom that gives away electrons turns into a positively charged cation.

- The atom that receives electrons turns into a negatively charged anion.

The bond that exists is the strong force of attraction between the positively charged cation and negatively charged anion which is called electrostatic force. Example of ionic bond is table salt (sodium chloride, NaCl).

Tip: That ionic compounds do not consist of separate molecules is revealed in the fact that they organize themselves in many layers and repeat such structures known as crystal lattices. To enrich your knowledge of the interactions occurring and the resulting characteristics, [Learn more about ionic bonding] (Future Article Link: /ionic-bonding/).

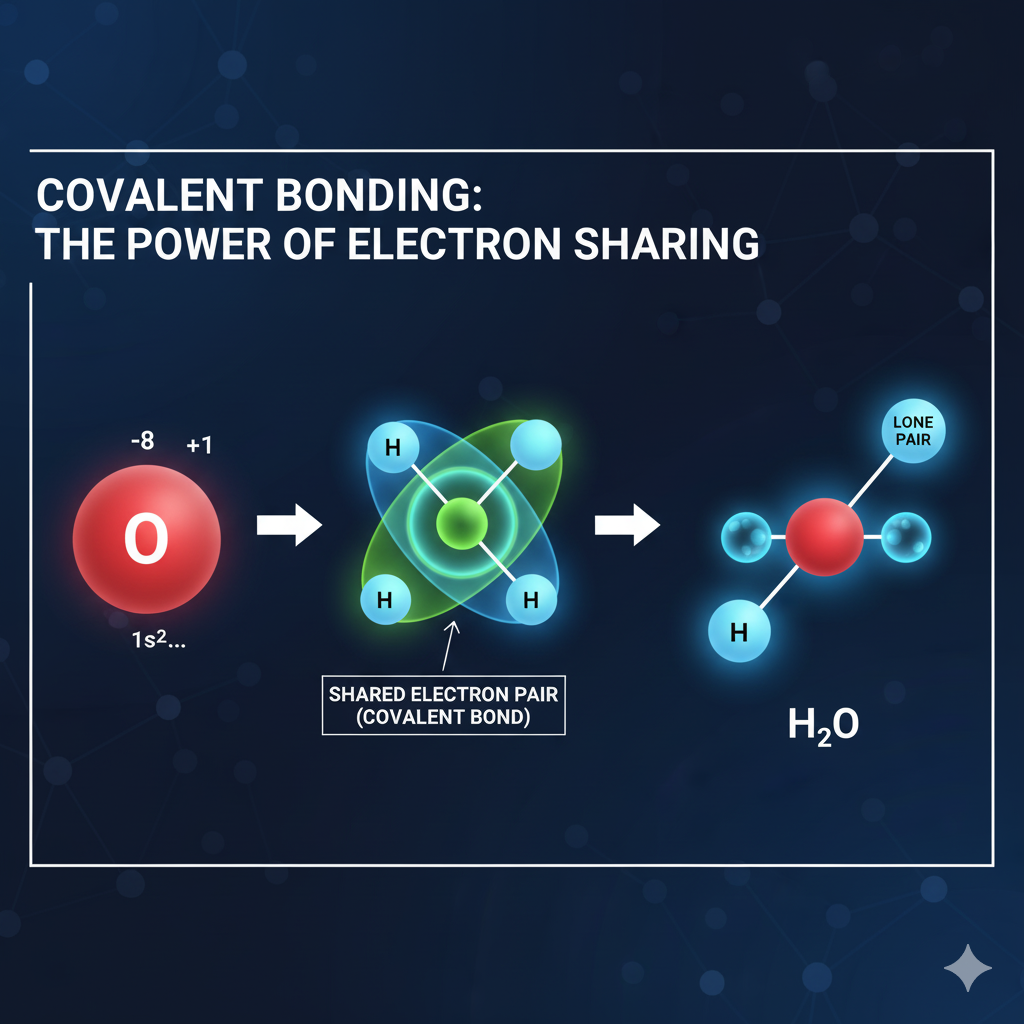

Covalent Bonding: The Power of Electron Sharing

Covalent bonds are generated through the sharing of electrons between two atoms, usually two non-metals. The electrons shared are counted by both atoms as part of their stable octet.

The bond between electrons is stronger than that of ionic and thus covalent compounds create molecules which are separate neutral groups of atoms. The proportion of a covalent bond’s strength is defined by the number of shared electron pairs:

Single, Double, and Triple Bonds

- Single Bond: A single pair of electrons is shared (for example, H – H).

- Double Bond: Sharing comprises two pairs of electrons (for example, O = O).

- Triple Bond: Three pairs of electrons are shared (for example, N ≡ N).

Coordinate Covalent (Dative) Bonds

A unique covalent bond in which one atom supplies both of the shared electrons. This is usually the case with polyatomic ions (such as the ammonium ion, NH4).

Real-World Focus: Covalent bonds are the basis of life, they generate water, sugar, and DNA. [Learn about the formation of covalent bonds in your everyday substances] (Future Article Link: /covalent-bonding/).

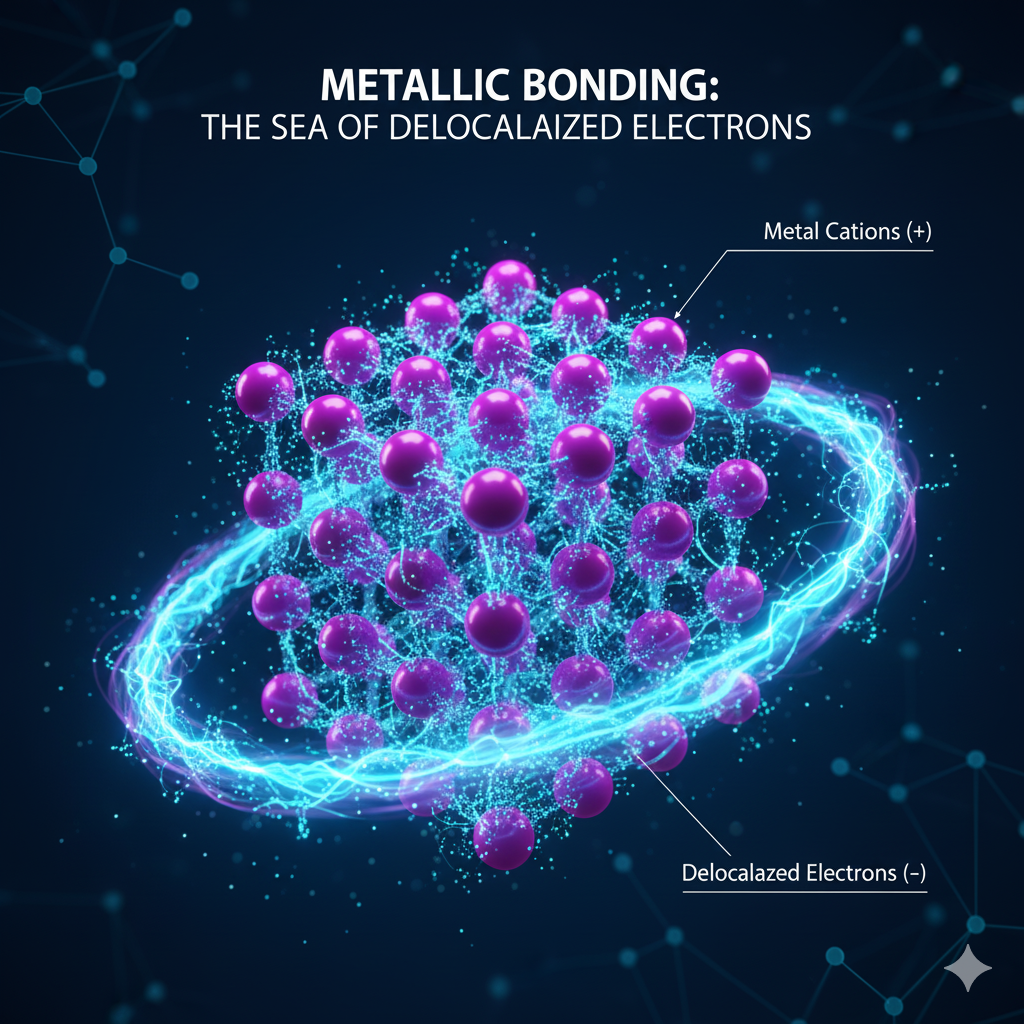

Metallic Bonding: The Sea of Delocalized Electrons

Metallic bonds are very peculiar and are the only type of bond that is found in metals (for instance, gold, copper and iron). These bonds are the main reason for the general properties of metals like conductivity, malleability, and shining.

In a metal solid, a metal atom emits its valence electrons, which are not confined to that one atom. Rather, these electrons are mobile and can circulate around the positive metal ions, which in turn gives rise to the term “electron sea.”

The metallic bond is made up of the force that pulls the positively charged ions of the metal towards the free flowing electrons that constitute a negative charge.

Materials science: The distinctive formation of metallic bonds is the reason that copper wire is a superior conductor of electricity. Want to know more about it? Take a look at our [Detailed guide on metallic bonding and its properties] (Future Article Link: /metallic-bonding/).

Weak Intermolecular Forces

The previous types of bondings are the ones that connect atoms within a molecule (intramolecular) while intermolecular forces (IMFs) are the weakest between separate molecules.

These forces are of great importance as they are the ones that determine physically the melting and boiling points of a substance among others.

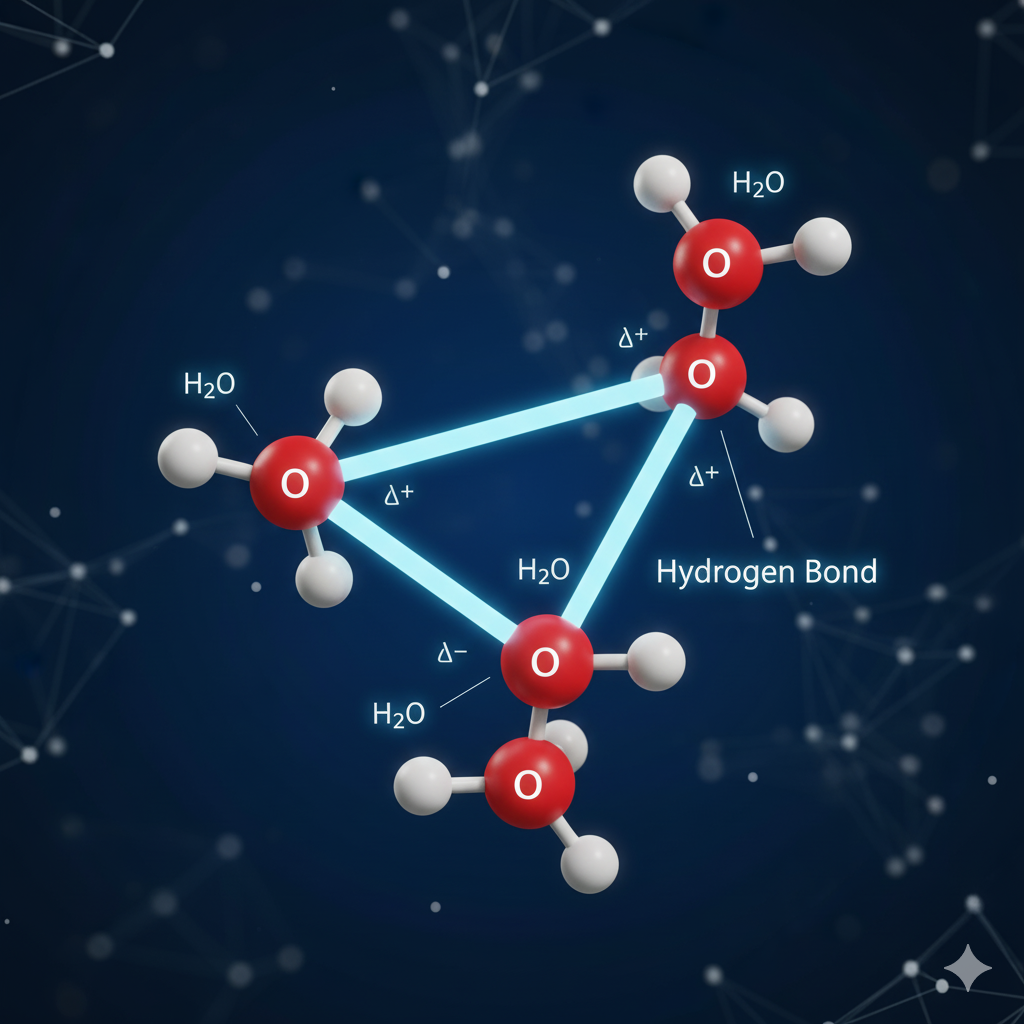

Hydrogen Bonding

The strongest type of IMF is this one. It is not really a bond but rather a vigorous dipole-dipole attraction that arises when hydrogen (H) is directly connected to a highly electronegative atom among the following: Nitrogen (N), Oxygen (O), or Fluorine (F).

Hydrogen bonds play a key role in biology, being the forces that connect the two strands of the DNA double helix. [Understand hydrogen bonding with simple biological examples] (Future Article Link: /hydrogen-bonding/).

Van der Waals Forces (Dipole-Dipole, London Dispersion)

This category contains the weaker forces:

- Dipole-Dipole Forces: Attraction between the polar molecules’ oppositely charged ends.

- London Dispersion Forces (LDF): Weak, temporary forces created due to the momentary displacement of electrons which results in the formation of temporary dipoles. These forces are present in all types of molecules (polar and non-polar) but in non-polar molecules like CH4, they are the only IMFs that exist in non polar molecules.

Advanced Theories of Chemical Bonding

The first step in comprehending the various bonds types is understanding them. Subsequently, the theories that explain the reasons behind the specific molecular shapes, the real sharing or transferring of the electrons, will be explored. These concepts are very important in the prediction of chemical reactivity.

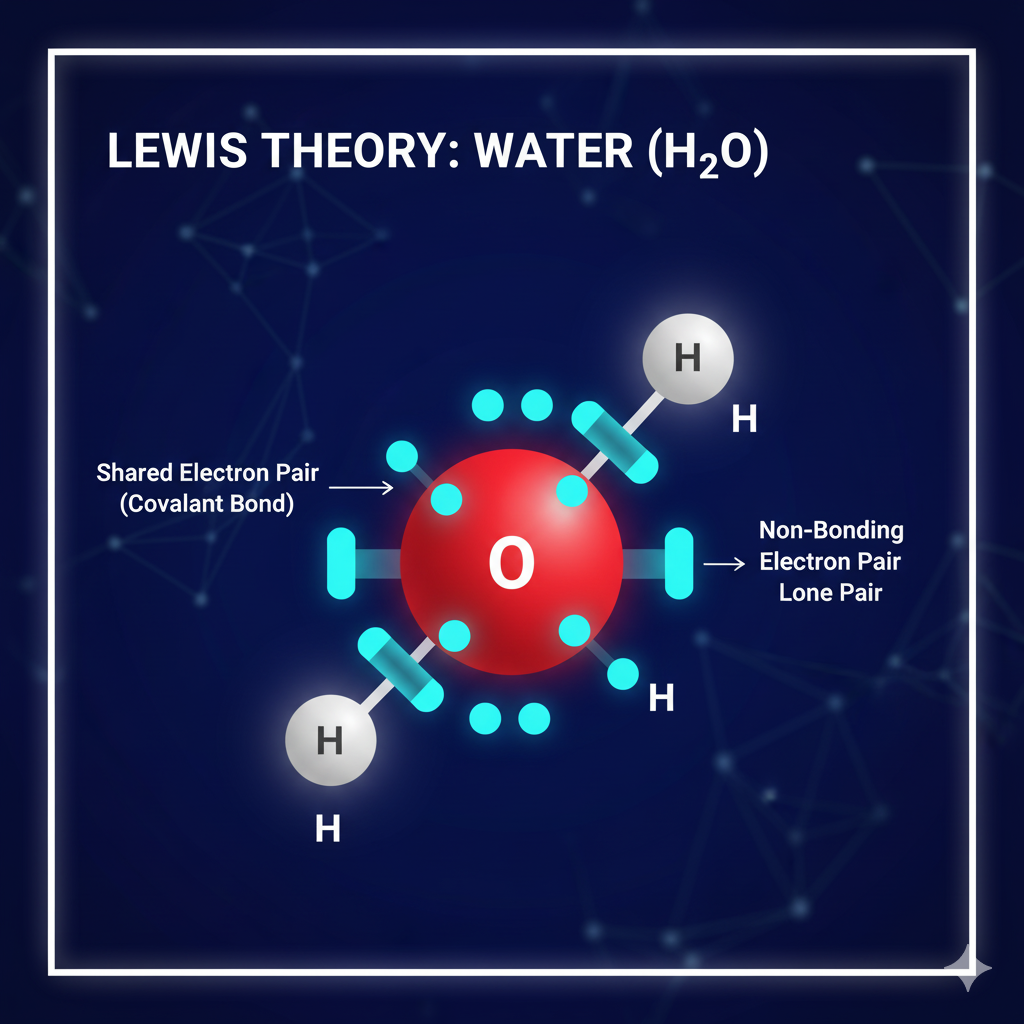

The Lewis Theory and Kossel-Lewis Approach

The major source of modern bonding theory originated from the combined efforts of Gilbert N. Lewis and Walther Kossel.

- Lewis Theory: Centers on the idea of sharing electron pairs to reach a noble gas configuration (the Octet Rule). This is illustrated using Lewis structures, diagrams that show the bonding and non-bonding (lone pair) valence electrons in a molecule.

- Kossel’s Theory: Particularly dealt with the creation of ionic bonds through the total transfer of electrons, which results in the formation of ions that are then held together by electrostatic forces.

In conjunction, the Kossel-Lewis Approach presents a straightforward prediction model for the electron bookkeeping in a large number of usual compounds.

Theoretical Depth: To fully apprehend the basic laws underlying the sharing and transfer of electrons, [Read our full explanation of Lewis Theory and Kossel-Lewis Approach] (Future Article Link: /lewis-theory-of-bonding/).

Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) Theory: Predicting Molecular Geometry

VSEPR theory is a basic but very effective model that aids in predicting the spatial arrangement (or molecular geometry) of molecules in three dimensions.

Its fundamental assumption is that the electron domains (that is, bonding pairs and lone pairs) surrounding a central atom will do so in a manner that they are the most distant from each other thus, minimizing the repulsion forces between electrons. This repulsion is the one that determines the bond angles and the resulting shape (like, linear, trigonal planar, tetrahedral, etc.) of the molecule.

Valence Bond Theory and Hybridization

Though VSEPR clarifies the shape, the Valence Bond (VB) Theory describes how the bonds are made. It argues that a covalent bond comes into being through the overlap of atomic orbitals (s, p, d) that are half-filled on two distinct atoms.

One of the key ideas of the VB Theory is Hybridization. Since the simple atomic orbitals often do not fit the observed molecular shapes, hybridization claims that atomic orbitals combine to create new, equal hybrid orbitals (sp3, sp2, sp, etc.). These hybrid orbitals are positioned in space in the same way as the geometry suggested by VSEPR.

Orbital Mechanics: For a comprehensive understanding of the wave-mechanical models of bonding, including the intricacies of sigma (σ) and pi (π) bonds, [Dive deeper into Valence Bond Theory and Molecular Orbitals] (Future Article Link: /valence-bond-theory/).

Quantifying the Bond: Key Characteristics

Chemical bonds are not merely in the condition “on” or “off,” they exhibit properties that can measure their strength, length, and energy.

Bond Length and Bond Angle

Bond Length: The average distance separating the nuclei of the two atoms in a molecule that are held together by a chemical bond. Stronger are generally the shorter bonds.

Bond Angle: The angle created by two neighboring bonds in a molecule. The bond angle is a direct result of the molecular geometry that is determined using VSEPR Theory.

Bond Enthalpy (Bond Energy) and Bond Order

Bond Enthalpy (or Bond Energy): The measure of energy that is needed to cleave one mole of the particular bond. High bond enthalpy indicates that the bond is strong and stable.

Bond Order: The quantity of chemical bonds between a pair of atoms. (Single bond = 1, Double bond = 2, Triple bond = 3). A higher bond order translates into a stronger, shorter bond.

Resonance and Delocalization

Certain molecules cannot be represented correctly with a single Lewis structure. Resonance is a situation where the actual structure is the average (or hybrid) of two or more equivalent structures (known as canonical forms) that are possible. This phenomenon usually involves electrons that are shared over several atoms and this makes the molecule more stable and of lower energy.

Strength and Stability: The properties of a bond that can be measured are essential in predicting the reaction outcomes. [Understand how bond length and bond energy affect molecular strength] (Future Article Link: /bond-characteristics/) to become proficient in molecular stability.

Real-World Importance of Chemical Bonding

Chemical bonding is not an abstract theory; it’s the engine of the physical world.

- The ability of Carbon to form four strong covalent bonds (hybridization) creates the immense structural diversity necessary for organic chemistry and all living things.

- Hydrogen bonding is responsible for the unique properties of water (high boiling point, surface tension), which makes life on Earth possible.

- Metallic bonding is what allows engineers to design materials with specific strengths and conductivities for buildings and electronics.

[See real-world examples of bonding in chemistry experiments] (Future Article Link: /applications-of-chemical-bonding/) and find out how these fundamental concepts are applied in laboratories and industries.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Atoms react to achieve a more stable, lower-energy electronic configuration, most commonly by satisfying the Octet Rule (having eight valence electrons). They achieve this stability either by transferring electrons (forming ionic bonds) or by sharing electrons (forming covalent bonds).

The forces are the chemical bonds themselves:

- Ionic bonds are held together by the strong electrostatic force of attraction between positive ions (cations) and negative ions (anions).

- Covalent bonds are held together by the mutual attraction of the two positively charged nuclei for the shared pair of electrons between them.

Hybridized orbitals are new, equivalent orbitals formed by the mathematical mixing of an atom’s pure atomic orbitals (s, p, d). Their use is to explain the observed molecular geometry and equivalent bond angles in molecules. For example, the mixing of one s and three p orbitals creates four equivalent sp3 orbitals, perfectly explaining the tetrahedral shape of methane CH4).

The paramagnetism of O2 (meaning it’s attracted to a magnetic field) cannot be explained by simple Lewis or Valence Bond Theory. It is explained by Molecular Orbital (MO) Theory, which predicts that the oxygen molecule has two unpaired electrons in its antibonding orbitals. Substances with unpaired electrons are paramagnetic.

Need Extra Help with Bonding?

Concepts like hybridization and VSEPR can be tough. Don’t struggle alone.

Chemistry Tutor Hub is your tutor marketplace. Find expert teachers specializing in Chemical Bonding to get the personalized support you need to succeed.

Find Your Tutor Now on Chemistry Tutor Hub.